The Descent

The interactive game starts. Pleasure, nil. Pain, nil.

He’s tired of procrastinating. He spends hours daydreaming about pursing his dream of being a creator, facing his demons, and mastering himself. He finally sits in front his computer, stares at a blank screen to begin planning and wonders why his mind has just gone blank. The wall of resistance is quelling his ability for deep work and to feel pleasure and the fear of punishment begins to set it. There’s just too much uncertainty.

Pleasure, 0. Pain, 1.

The pain from being in a state of overthinking, analysis paralysis and resistance outgrew the reward and he needed to return to a balanced state of allostasis with a quick fix.

He opened up Twitter to gauge some inspiration from creators that he wanted to be like. Maybe he can get some new pleasurable ideas. The algorithms bias to survivorship and hyperbolic discounting showed him the most popular creators using professional grade production with millions of followers, tens of thousands of likes and retweets. He automatically compared their popularity to his own and felt like a loser whilst craving to be desired just like them. No followers, no likes and no retweets. His bias towards comparison turned his search for inspiration into a state of insecurity through intimidation. He felt like he couldn’t compete. Why even try?

Pleasure: 0, Pain, 2.

He switched to TikTok as his previous search for pleasure produced unexpected pain. Scrolling infinitely he felt pangs of pleasure at first. Being sucked into the vortex, the pangs turned into chronic overstimulation and just like ice cream, with the first lick feeling amazing, the consecutive licks became less and less pleasureful. The depletion of pleasure gave way for the pain to seep in.

Pleasure, 1. Pain, 3.

Nudging himself to the present, he reverted back to his blank screen and his availability bias reminded him of his previous encounter with comparison and overstimulation. The goal of planning his dreams became too daunting. He logs off into the void of escapism.

Game over. It’s a loss. Pleasure, 2. Pain, 4.

Maybe his dreams can wait another time.

Evolution

Social media can have a positive impact on our wellbeing through connecting with others, finding inspiration and keeping in touch with family. There are however, no shortage of downfalls.

We humans were never designed to live in cities. It wasn’t until end of the Agricultural Revolution and the start of the Cognitive Revolution that we began seeing others as strangers. The predicted average group size in traditional human cultures was 150, referred to as Dunbar’s Number [1]. Now that number is infinite. Traditionally we only needed to compare ourselves to our immediate tribe and now we have the privilege of comparing ourselves to billions of people with their highlight reels. Once that 150 threshold is crossed, things begin to work differently. You cannot run a division with thousands of soldiers the same way you run a platoon, so we invented common myths. Any large-scale human cooperation–whether a modern state, a medieval church, an ancient city or an archaic tribe–is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination [2].

If happiness is determined by expectations, then two pillars of our society – mass media and the advertising industry – may unwittingly be depleting the globe’s reservoirs of contentment. If you were an eighteen-year-old youth in a small village 5,000 years ago you’d probably think you were good-looking because there were only fifty other men in your village and most of them were either old, scarred and wrinkled, or still little kids. But if you are a teenager today you are a lot more likely to feel inadequate. Even if the other guys at school are an ugly lot, you don’t measure yourself against them but against the movie stars, athletes and supermodels you see all day on television, Facebook and giant billboards [3].

Our primitive emotions were never designed to handle the unlimited supply of fake news, outrage, algorithmic bias and the fear of missing out. Our search for inspiration on social media quickly turns into envy as we have an unlimited supply of scrolling. Dopamine was the engine of success for our ancestors. It gave us the ability to create tools, invent science, plan for the future and made us the dominant species on the planet after living in scarcity and on the brink of extinction. In the modern age of abundance however, dopamine is continuing to drive us forward, perhaps to our own destruction.

Technology develops fast while evolution is slow. Our brains evolved at a time when survival was in doubt. That’s less of a problem in the modern world, but we’re stuck with our ancient brains. It’s possible that we won’t last beyond another half-dozen generations. We’ve simply become too good at gratifying our dopaminergic desires: not all forms of more and new and novel are good for an individual, and the same is true for a species. Dopamine doesn’t stop. It drives us ever onward into the abyss [4].

Exclusion

Illusive SAAS Loss Aversion Model and the War Against Creators

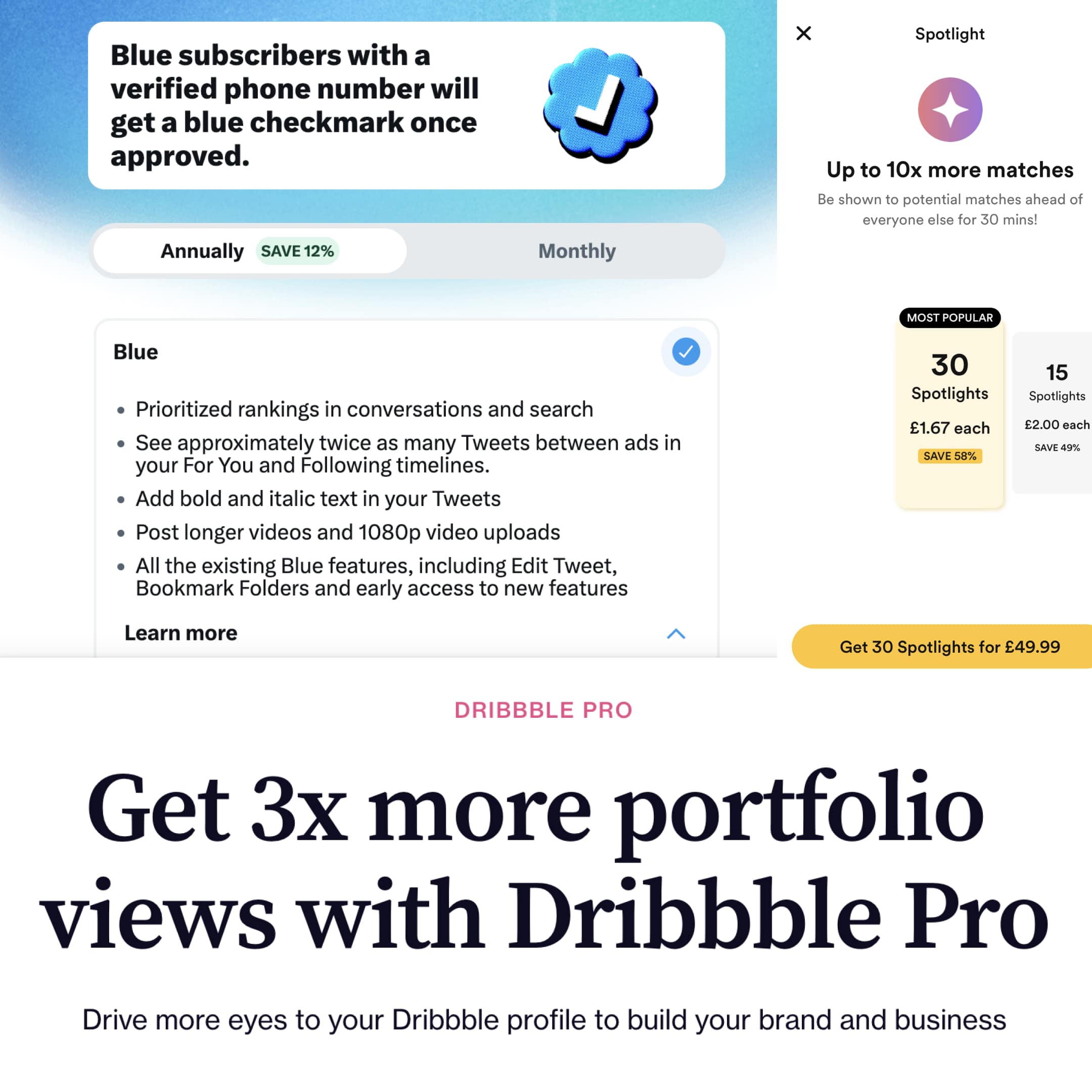

User experience has been gamified and converted into a new business model. The more you pay the better the user experience. We have reached a dire state in design where engagement is now being charged per interaction. An example being apps like Tinder charging a one-off payment for 24 hour boosted exposure, unlimited swipes and ‘who liked you’ reveals.

Many popular social platforms today seem to employ the same uncreative, illusive business model of choosing profit over user experience and the wellbeing of their users. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Tinder, Bumble and even Dribbble promise free usage of their product. Creators invest thousands of hours engaging with communities, building a large following and also building the platform itself through network effects only to have the algorithm exploit their bias towards loss aversion. Creators are hit with the wall and told that their reach is limited, requiring a payment to continue.

The function of this illusive business model is to hook [5] us through the freemium model exploiting our biases towards hyperbolic discounting, conformity or negativity. Nudge us to contribute and share through salience, framing and anchoring. Polarize us through verification [6]. Then tarnish the entire user experience, limiting our exposure and reach through loss aversion, scarcity and the aforementioned biases that got us hooked in the first place. Our reach in search results, timelines and replies are deprioritized leading us to distorted thoughts about being excluded and FOMO. Finally we are taunted with blurred images and obfuscated text of how close we are to avoiding the loss and what we are missing out on. This is not what we signed up for.

Comparison

There is a tragic trend in the world of tech where apps attempt to match the competition and alienate their own user base. Facebook copies TikTok, Facebook copies Twitter, Facebook copies SnapChat and so forth. This is due to the lack the creativity and originality to innovate by blindly copying the features of their competitors in an attempt to lure their rivals user base to their own platform. This form of competition-driven design is one of the reasons why illusive design has become so prevalent as these copycats are exposing and reinforcing so many interactive patterns to users that are not well thought out. Platforms like the App Store are saturated with millions of apps competing for consumers attention.

Starting with a few hundred apps at its start, the App Store now has several million apps, all competing for consumer attention. As a result, app developers are locked in furious competition. It’s not enough to be a good, useful app–they have to actively take away attention from other hyper-addictive apps that have been optimized over years to engage users. It’s a zero-sum game between the millions of apps in the Apple App Store and Google Play store. No wonder the top app charts now rarely change, and are mostly dominated by large, established products [7].

The state of tech would be much better off if they focused on their strengths rather than weaknesses. Users tend to age over time and companies need to keep the retention up every quarter to satisfy their investors and ever-changing audience.

Harvard professor Youngme Moon argues that it is this attempt to match the competition that causes all products to be the same. When companies try to increase sales by matching every feature of their competitors, they end up hurting themselves. After all, when products from two companies match feature by feature, there is no longer any reason for a customer to prefer one over another. This is competition-driven design. Unfortunately, the mind-set of matching the competitor’s list of features pervades many organizations. Even if the first versions of a product are well done, human-centered, and focused upon real needs, it is the rare organization that is content to let a good product stay untouched. Most companies compare features with their competition to determine where they are weak, so they can strengthen those areas. Wrong, argues Moon. A better strategy is to concentrate on areas where they are stronger and to strengthen them even more. Then focus all marketing and advertisements to point out the strong points. This causes the product to stand out from the mindless herd. As for the weaknesses, ignore the irrelevant ones, says Moon. The lesson is simple: don’t follow blindly; focus on strengths, not weaknesses. If the product has real strengths, it can afford to just be “good enough” in the other areas [8].

As creators, we assume that success will come fast as our worldview is distorted through highly curated algorithmic content. We only see the most popular videos, tweets and posts with thousands of likes and assume with the support of our bias towards survivorship that we can achieve instant success with our first post. What the algorithm isn’t telling us is that the content pushed to the top of the queue has been cherry picked from hundreds of failed videos that have spent years experimenting on finding market fit.

Social platforms are pushing us to connect less with our friends and more with brands and influencers. These influencers are hired to prey on those who are impressionable and sell products that they themselves most likely do not use. Our bias towards authority makes us feel that they know what they’re talking about and our bias towards affinity increases the likelihood that we’ll buy as they surely understand what we are going though.

Comparison turns an iterative game into a race to the bottom.

Mental Health

Teen anxiety, depression and suicide rates have risen sharply in the last few years. Hatred has become widespread proliferating extremists from the far left and right. We now retreat into our self-confirmatory bubbles amplified by extremists and trolls intent on polarizing us and them [9]. The rapid growth of social media in the years after the iPhone was released allowed teens to check in on their social media status every few minutes, and many did [10].

For a long time, studies have shown that girls have higher rates of depression and anxiety than boys do after puberty. Since 2011, as social media was taking off, the rates of depression began increasing. In 2016, roughly one in every five girls reported having a major depressive episode [11].

What is it specifically about social media that is causing such destruction?

The first is that social media presents “curated” versions of lives, and girls may be more adversely affected than boys by the gap between appearance and reality. Many have observed that for girls, more than for boys, social life revolves around inclusion and exclusion. Social media vastly increases the frequency with which teenagers see people they know having fun and doing things together-including things to which they themselves were not invited. While this can increase FOMO (fear of missing out), which affects both boys and girls, scrolling through hundreds of such photos, girls may be more pained than boys by what Georgetown University linguistics professor Deborah Tannen calls “FOBLO” – fear of being left out? When a girl sees images of her friends doing something she was invited to do but couldn’t attend (missed out), it produces a different psychological effect than when she is intentionally not invited (left out). And as Twenge reports, “Girls use social media more often, giving them additional opportunities to feel excluded and lonely when they see their friends or classmates getting together without them.” The number of teens of all ages who feel left out, whether boys or girls, is at an all-time high, according to Twenge, but the increase has been larger for girls. From 2010 to 2015, the percentage of teen boys who said they often felt left out increased from 21 to 27. For girls, the percentage jumped from 27 to 40. Another consequence of social media curation is that girls are bombarded with images of girls and women whose beauty is artificially enhanced, making girls ever more insecure about their own appearance. It’s not just fashion models whose images are altered nowadays; platforms such as Snapchat and instagram provide “filters” that girls use to enhance the selfies they pose for and edit, so even their friends now seem to be more beautiful. These filters make noses smaller, lips bigger, and skin smoother.” This has led to a new phenomenon: some young women now want plastic surgery to make themselves look like they do in their enhanced selfies [12].

The generic social platform consists of a feed where user generated content can illicit FOMO using curated highlight reels and variable rewards from the mix of mundane and relevant content [13]. However there’s also the platforms that enable pathological behavior such as narcissism through the use of beauty filters leading victims to compare their flawed features to the features of the flawless. To conform and avoid being left out, others use and promote these filters leading to a recursive viral loop of exposure. The engagement algorithm then picks this up and places it at the front of the most trending as it assumes that is what the people want. Viewers are then consuming this content, mistaking augmented reality from reality and diminishing their self esteem.

What other interactions directly affect our sense of reality and wellbeing? Other popular social components consist of a leader/follower and an upvote/downvote interface that fluctuates arbitrarily. What kind of distorted overgeneralizations are our minds exposed to when seeing a update? When a new follower is received, we get a dopamine hit receiving validation that our social status has been elevated. The follower however, could be a bot, a troll, a user posing as someone else, a user wanting a superficial follow back or even a browser caching issue.

When a follower is lost we are left jumping to conclusions about whether we did something wrong as we feel a sense of rejection when the loss could have been the removal of bots from an algorithm update

Social media is leaded pipes for today’s children – Jonathan Haidt

When swiping on Tinder, we wonder whether these profiles are real, fake or abandoned. Are we wasting our time? Do they still use it or have they given up? How accurate does this person’s profile reflect their real life? There is no way to verify this accurately.

Common interactions on dating apps eventually lead to pathological behavior through ghosted messages whilst being a perfect playground for psychopaths looking for their next prey. Swiping profiles becomes a numbers game through matches for the ultimate award of high self-esteem. Being inundated with profiles where intentions differ from the bio, it leaves one in a distorted state of affairs.

We have TikTok causing Tourette syndrome for girls [14], glorifying context switching, depleting our dopamine reserves and doctors actually mistaking this behavior for ADHD [15].

Just like the social feed, these superficial interactions have consequences in the long run that exploit our biases and elevate distorted thinking patterns as they do not reflect the core design principle of matching real world conventions. Dark patterns do not cover this.

Dopamine

It’s a scientific fact that spiking your dopamine levels lowers the baseline leading to an equivalent spike in pain afterwards. The problem is that we are not aware of the pain [16] that follows when we are in the moment and we spiral into catastrophizing about why we feel this way. The unintended pain is accompanied with a lack of motivation, sadness and apathy. To rebalance this imbalance we initiate the recursive loop of chasing dopamine seeking more stimulation. The illusion is that pain is the symptom in the pursuit of the more chemical and not the cause.

By mapping notifications to real world conventions, we can see the equivalence to slot machines in casinos. The unpredictability becomes an addiction as we are manipulated into thinking that this interaction is benign rather than malevolent. If we keep on pressing the lever we’ll eventually get to the reward.

Do we check social media for fulfillment or for the pleasure of relieving the unpleasant feeling of craving? [17]

What big tech doesn’t tell us about the impulsive chase for pleasure is that pain is waiting for us just around the corner behind the like button [18]. Even startups today are joining YC to help combat tech addiction with chrome extensions and removing the pleasurable colors on smartphones by converting to grayscale is becoming another countermeasure [19]. We users are the product, like rats in a caged experiment. We get a dopamine surge every time a pallet of food is dropped. However the surge stops if we expect the food to drop every 5 minutes as there is no surprise and no error in the prediction of a reward. Dropping the pallet at random times is the trick as the surge arises during the anticipation of the reward [20].

When you watch sports, you can be inside the team, experiencing the game the way the team does. Cars not only will drive themselves to make you safer, but provide lots of entertainment along the way. Video games will keep adding layers and chapters, new story lines and characters, and of course, 3D virtual environments. Household appliances will talk to one another, telling remote households the secrets of our usage patterns. The design of everyday things is in great danger of becoming the design of superfluous, overloaded, unnecessary things [21].

There is a specific formula used in the world of tech that serves as an elegant way to understand what drives our actions towards instant gratification [22]. Devised by Dr. B. J. Fogg, Director of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University, B = MAT represents that a given behavior will occur when motivation, ability, and a trigger are present at the same time and in sufficient degrees [23]. If any component of this formula is missing or inadequate, the user will not cross the “Action Line” and the behavior will not occur.

These interactions are designed intentionally for the purpose of retention through pleasure. The accompanying pain is not a metric that is tracked. We get rewarded in these short term with signals such as hearts, likes, thumbs up and we conflate that with value and truth [24].

Habit

The issue with addictive interactions is the vortex of tolerance, also known as habituation. It’s hard to escape as we increasingly need more of the interaction to receive the same anticipatory hit as before [25]. Fostering consumer habits increase how long and frequently customers use a product, resulting in a higher customer lifetime value [26].

Facebook are notorious for getting users hooked in as early as possible. From Cambridge Analytica to the controversial targeting of under 13 year olds at the most vulnerable age. Children establish habits long before they learn to self regulate, making apps like Instagram for Kids the perfect opportunity to exploit their lack of awareness [27].

A chilling 2017 interview with Sean Parker, the first president at Facebook mentioned that their thought process at the early stage was to develop a social validation feedback loop to exploit the vulnerability in human psychology [28]. Sadly these social algorithms do not take into account our interests as humans [29]. The content we see in YouTube recommendations, Google’s page rankings, and social feeds are from those who have learned how to game the system.

We need to protect our time and energy so that we can focus on becoming the best versions of ourselves [30].

Flow

The pull of social engagement triggers and the anticipation of variable rewards makes it difficult for us to sustain flow that brings meaning and joy our lives [31]. Being in the state of flow requires concentration, energy, uninterrupted focus and a distractions free work environment. Whether we’re writing stories, designing products or producing music, limiting our exposure and being too accessible breaks our state of flow and saps our energy [32].

These services may not be the crucial backbone of our connected world as claimed. They are simply products created by private companies, well-funded and marketed to gather and sell personal information and attention to advertisers. While they can be enjoyable, they are merely frivolous distractions in the grand scheme of your life and goals, potentially diverting you from more meaningful pursuits [33].

We can achieve fulfillment at the end of the day through giving our minds more meaningful things to do, develop healthier habits and achieve allostasis rather than being semiconscious and giving our attention and energy to platforms that do not care for our values and boundaries.

Trust

Facebook and Twitter has the ability to distort our worldview by turbocharging rapid shifts in perceived consensus. They enable fringe actors to manufacture illusions by creating the impressions of majorities that do not exist in reality. The amplify the voices of the few and parade their opinions around as if they represent the majority when they are in fact victims of the survivorship bias [34].

Social media exacerbates the situation by amplifying the loudest voices, regardless of their expertise. On platforms like Twitter, a small minority of users, comprising just 10 percent of tweeters in the US, generates a vast 80 percent of all tweets. This vocal minority gains an advantage due to the absence of time and space constraints, leading others to believe they represent the majority. As people often mistake repetition, confidence, and volume for truth, the statements of this loud minority are perceived as accepted truths, irrespective of their accuracy [35].

Social media amplifies the friendship paradox, making a few highly connected individuals appear very popular and influential. Their opinions spread rapidly, giving the illusion of a majority view, even though they are not representative of most people. These loud voices often hold fringe opinions, and with the internet’s amplifying effect, the web becomes like a carnival room of distorting mirrors, making it challenging to discern truth from falsehood. Unless we take action to break free from this illusion, we unwittingly contribute to perpetuating these distortions [36].

Our biases towards survivorship and availability are magnified with these platforms and we can mitigate the consequences through awareness.

Bots are a huge bane for social platforms yet Twitter feels the need to keep them. These fake, automated accounts are designed to mimic certain human behaviors online including liking and sharing content. They have the ability to flood legitimate debates with their own arguments and creating the illusion of the majority. They massively multiply the ability for one person to manipulate a group of people [37].

Few people realize it, but a chilling 19 percent of interactions on social media are already between humans and bots, not humans and humans. Studies based on statistical modeling of social media networks have found that these bots only need to represent 5 to 10 percent of the participants in a discussion to manipulate public opinion in their favor, making their view the dominant one, held by more than two-thirds of all participants. When those on the powerful fringe–the Mrs. Salts of the world -enforce a position that doesn’t reflect reality, join together with general ignorance, or harness the silent support of all those waiting around to see which way the wind will blow, they can rapidly solidify into a distorted, hurricane-strength social force. wielding the influence of a majority with the true support of a meager few, the resulting collective illusion harnesses crowd power to entrap us in a dangerous spiral of silence [38].

Social apps are essentially social experiments with no regulation and are far more potent than government policy [39].

The Ascent

Taking deep breaths, he observed this thoughts and how his daily interactions made him feel. Counting how many times he felt good and felt bad from each interaction on and offline, the scale tipped heavily towards the negative and he knew from that moment, he’ll need to rebalance the scale by engaging in deep work and limiting his exposure to the illusive reminders.

Level Up Your Design Skills By Supporting This Unique Research On Substack

The content in this article is only a small portion of the 8,000 word essay exposing the unique world of illusive design. Consider subscribing to our Substack and get full access to 50+ unique illusive interaction patterns and how they exploit our biology and cognition along with real examples and solutions. Be part of the change and level up your skills. The research takes time to collect and the Substack will be a growing repository of new patterns where you won’t find anywhere else. Below is a small example of what you can get as a subscriber discussing one of the new ethical design heuristics along with 3 examples of illusive interactions.

References

- Harari, Y. (2011). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. [online] Vintage, p27. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23692271-sapiens [Accessed 09 Jan. 2022].

- Ibid.

- Harari, Y. (2011). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. [online] Vintage, p498. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23692271-sapiens [Accessed 09 Jan. 2022].

- Lieberman, D. (2018). The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity—and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race. [online] BenBella Books, p202. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38728977-the-molecule-of-more [Accessed 10 Jul. 22].

- Eyal, N. (2019). Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. [online] Penguin Business, p20. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22935795-hooked [Accessed 11 Jan. 2023].

- Simler, K. (2017). The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life. [online] Oxford University Press, p287. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/28820444-the-elephant-in-the-brain [Accessed 01 May. 2022].

- Chen, A. (2021). The Cold Start Problem. [online] Harper Business, p . Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/55338968-the-cold-start-problem [Accessed 06 Dec. 2022].

- Norman, D. (2002). The Design of Everyday Things. [online] Basic Books, p262. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/840.The_Design_of_Everyday_Things [Accessed 21 Jan. 2023].

- Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. [online] Penguin Books, p5. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/36556202 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. [online] Penguin Books, p30. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/36556202 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. [online] Penguin Books, p149. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/36556202 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. [online] Penguin Books, p154. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/36556202 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Eyal, N. (2019). Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. [online] Penguin Business, p108. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22935795-hooked [Accessed 11 Jan. 2023].

- Haidt, J. (n.d.). Jonathan Haidt Debates Robby Soave on Social Media. [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-4AAST_AdSg&t=2067s [Accessed 10 Aug. 2023].

- Huberman, A. (n.d.). Huberman Lab: Maximizing Productivity, Physical & Mental Health with Daily Tools on Apple Podcasts. [online] Apple Podcasts. Available at: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/huberman-lab/id1545953110?i=1000528586045 [Accessed 10 Aug. 2023].

- Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. [online] Holt Paperbacks, p342. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/327.Why_Zebras_Don_t_Get_Ulcers [Accessed 18 Jul. 2022].

- Lieberman, D. (2018). The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity—and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race. [online] BenBella Books, p47. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38728977-the-molecule-of-more [Accessed 10 Jul. 22].

- Eyal, N. (2019). Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. [online] Penguin Business, p101. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22935795-hooked [Accessed 11 Jan. 2023].

- Weinschenk, S. (2011). 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People. [online] New Riders Publishing, p28. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10778139-100-things-every-designer-needs-to-know-about-people [Accessed 08 Jan. 2023].

- Lieberman, D. (2018). The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity—and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race. [online] BenBella Books, p12. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38728977-the-molecule-of-more [Accessed 10 Jul. 22].

- Norman, D. (2002). The Design of Everyday Things. [online] Basic Books, p293. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/840.The_Design_of_Everyday_Things [Accessed 21 Jan. 2023].

- Weinschenk, S. (2011). 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People. [online] New Riders Publishing, p124. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/10778139-100-things-every-designer-needs-to-know-about-people [Accessed 08 Jan. 2023].

- Eyal, N. (2019). Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. [online] Penguin Business, p61. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22935795-hooked [Accessed 11 Jan. 2023].

- www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Chamath Palihapitiya, Founder and CEO Social Capital, on Money as an Instrument of Change. [online] Available at: https://youtu.be/PMotykw0SIk?t=1134 [Accessed 29 Jul. 2023].

- Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. [online] Holt Paperbacks, p343. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/327.Why_Zebras_Don_t_Get_Ulcers [Accessed 18 Jul. 2022].

- Eyal, N. (2019). Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products. [online] Penguin Business, p19. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/22935795-hooked [Accessed 11 Jan. 2023].

- Fridman, L. (n.d.). Lex Fridman Podcast: #291 – Jonathan Haidt: The Case Against Social Media on Apple Podcasts. [online] Apple Podcasts. Available at: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/lex-fridman-podcast/id1434243584?i=1000565224431 [Accessed 10 Aug. 2023].

- Haidt, J. (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. [online] Penguin Books, p147. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/36556202 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Harris, S. (n.d.). Making Sense with Sam Harris: #312 — The Trouble with AI on Apple Podcasts. [online] Apple Podcasts. Available at: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/making-sense-with-sam-harris/id733163012?i=1000603166437 [Accessed 10 Aug. 2023].

- www.youtube.com. (n.d.). How Future Billionaires Get Sht Done*. [online] Available at: https://youtu.be/ephzgxgOjR0?t=781 [Accessed 29 Jul. 2023].

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. [online] Grand Central Publishing, p205. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25744928-deep-work [Accessed 07 Dec. 2022].

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. [online] Grand Central Publishing, p193. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25744928-deep-work [Accessed 07 Dec. 2022].

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. [online] Grand Central Publishing, p209. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/25744928-deep-work [Accessed 07 Dec. 2022].

- Rose, T. (2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. [online] Hachette Go, pxxii. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58340695 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Rose, T. (2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. [online] Hachette Go, p138. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58340695 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Rose, T. (2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. [online] Hachette Go, p140. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58340695 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Rose, T. (2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. [online] Hachette Go, p67. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58340695 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Rose, T. (2022). Collective Illusions: Conformity, Complicity, and the Science of Why We Make Bad Decisions. [online] Hachette Go, p68. Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58340695 [Accessed 17/05/2023].

- Peterson, J. (n.d.). Enlightenment and the Righteous Mind | Steven Pinker and Jonathan Haidt | EP 198. [online] www.youtube.com. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4tAQM5uU8uk&t=3705s [Accessed 10 Aug. 2023].